A rainy morning in Wellington turned tragic for Joshua Bowles, a 37-year-old father of five, who fell six metres from a Taranaki Street roof while working for Prowash, a local cleaning company. The accident, which shattered his body and future, has now cost Prowash a $120,000 fine for failing to keep him safe. At One Network Wellington Live, we tell this sobering story, revealing how a simple job went wrong and why workplace safety remains vital in our city.

Bowles started at Prowash just two months before the incident. He took the job hoping for more time with his young family, drawn by the company’s promise of flexible hours. On that fateful day, he joined the company director to test a new cleaning product on a commercial building’s roof. The task appeared straightforward. But Bowles lacked experience in roofing or working at heights. No one had trained him on safety harnesses or roof anchors. A course was planned, yet it was set for two weeks later. For Bowles, those weeks never came.

The job began like countless others. Bowles and his boss climbed scaffolding to reach the roof. They believed the site was safe. However, a crucial warning—an unsafe scaffold tag—escaped their notice. They slipped under a barrier, thinking nothing of it. The plan was clear: stay within the area guarded by edge-protection scaffolding. Bowles received instructions to remain in this safe zone. Carrying equipment, including hard hats neither man wore, he moved cautiously. Then, disaster struck. Bowles stepped beyond the protected area, slipped on the wet iron roof, and plummeted to the street below.

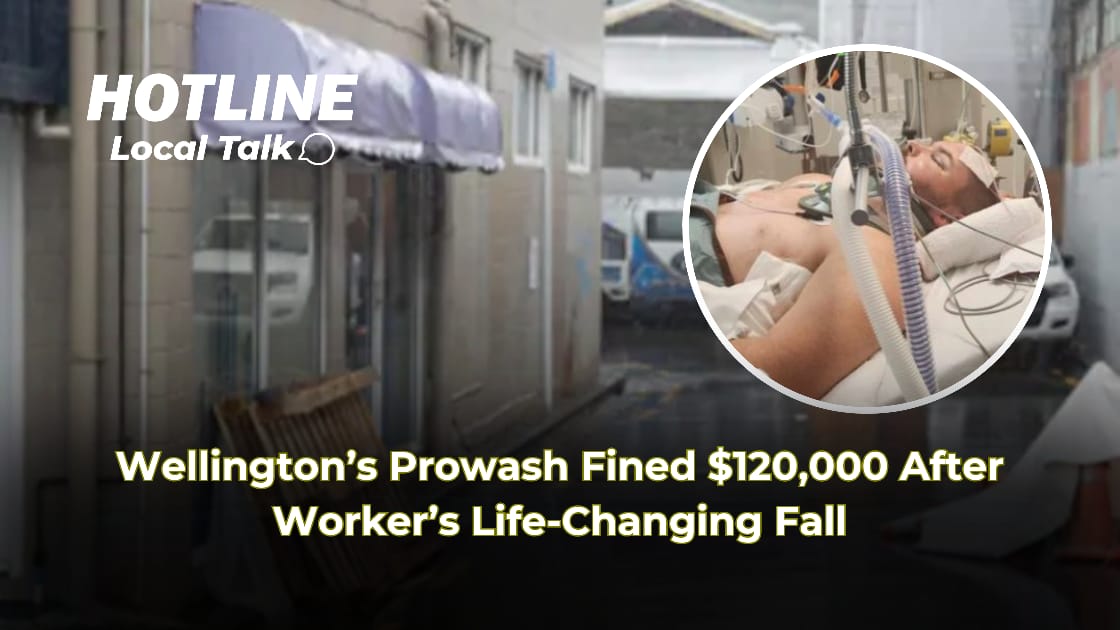

A passerby spotted him lying face down on Hopper Street, still and silent. Rain poured down. The Prowash director hurried to his side, joined by two nearby shop workers who held umbrellas to shield Bowles from the weather. An ambulance raced him to Wellington Hospital’s intensive care unit. His injuries were catastrophic. A traumatic brain injury threatened his recovery. Fractures tore through his clavicle, skull, face, ribs, neck, and femur. His teeth were damaged beyond repair. For six months, Bowles moved between four hospitals, including Christchurch’s Burwood Spinal Unit. His life, once filled with family moments, became a blur of pain and uncertainty.

The Wellington District Court later heard the toll of Bowles’ suffering. His victim impact statement, read on his behalf, laid bare the emotional wreckage. He spoke of guilt, feeling he had failed his family. As a father, he mourned missing his children’s birthdays, school events, and quiet evenings at home. Before Prowash, Bowles had declined a job at KiwiRail, swayed by the cleaning company’s promise of better hours. That choice haunted him. The court listened, gripped by the weight of his loss, a stark reminder that workplace accidents ripple far beyond the moment of impact.

Prowash faced justice in court. WorkSafe, the agency enforcing workplace safety, charged the company with breaching the Health and Safety at Work Act. The evidence was damning. Prowash had no proper safety policies. Risk assessments were nowhere to be found. On the day of the fall, they trusted incomplete scaffolding, ignoring obvious dangers. Bowles, untrained and new, was sent onto a slippery roof to test an unproven product. WorkSafe’s prosecutor pointed to photos on Prowash’s website, showing workers on roofs without harnesses. The company’s claim of a solid safety record rang hollow.

The defence expressed regret, arguing Bowles was told to stay within the safe zone. But the court saw the truth. Prowash admitted guilt, and the judge delivered a fine of over $120,000. The penalty hit hard, but for Bowles, no sum could restore what he lost. His recovery stretches on, a daily struggle with physical and emotional scars. The case, though, speaks louder than the fine. Safety isn’t optional. In Wellington, where small businesses like Prowash dot the landscape, neglecting it can ruin lives.

The court hearing unfolded with clarity. WorkSafe laid out the facts: Prowash failed to assess risks, train staff, or ensure proper equipment. The unsafe scaffold tag, missed by both workers, was a red flag ignored. The judge noted the company’s lack of systems, calling it a preventable failure. Prowash’s guilty plea acknowledged their role, but the courtroom’s focus stayed on Bowles. His statement, though read by another, carried his voice—a father broken by an avoidable mistake. The fine, while substantial, was secondary to the human cost laid bare.

This wasn’t just a legal reckoning. It was a wake-up call for Wellington. Workers like Bowles take jobs trusting their employers to protect them. When that trust breaks, families pay the price. Communities feel the strain. At One Network Wellington Live, we’ve covered too many stories of preventable pain. Each one dims the city’s spirit. Bowles’ fall exposed a hard truth: employers must do better. His story demands it.

The ruling offers some closure, but the work continues. Wellington’s businesses need robust safety plans, from training to risk checks. Workers deserve to go home whole. For Bowles, the path forward is tough. His family stands by him, but the moments he misses—school plays, bedtime stories—cut deep. The city he called home now holds a different meaning, shaped by a fall that didn’t have to happen.

Prowash’s fine draws a line: negligence carries consequences. But the real cost lies in Bowles’ fractured life. His story, raw and urgent, pushes us to act. Wellington thrives on its people—dedicated, hopeful, and strong. Keeping them safe starts with responsibility. At One Network Wellington Live, we’ll keep shining a light, demanding accountability. No worker, no parent, no Wellingtonian, should face what Bowles did. His fall reminds us why safety must come first, always.